It’s All in the Idea….

Okay. You’re really working the 8 Pages hard — but you’re still not seeing a smooth conversion from a noodled doodle to an actual character concept development.

Perhaps these five steps will help you on this journey to an imaginative adventure!

Five Simple Steps to Designing a Character You Actually Like

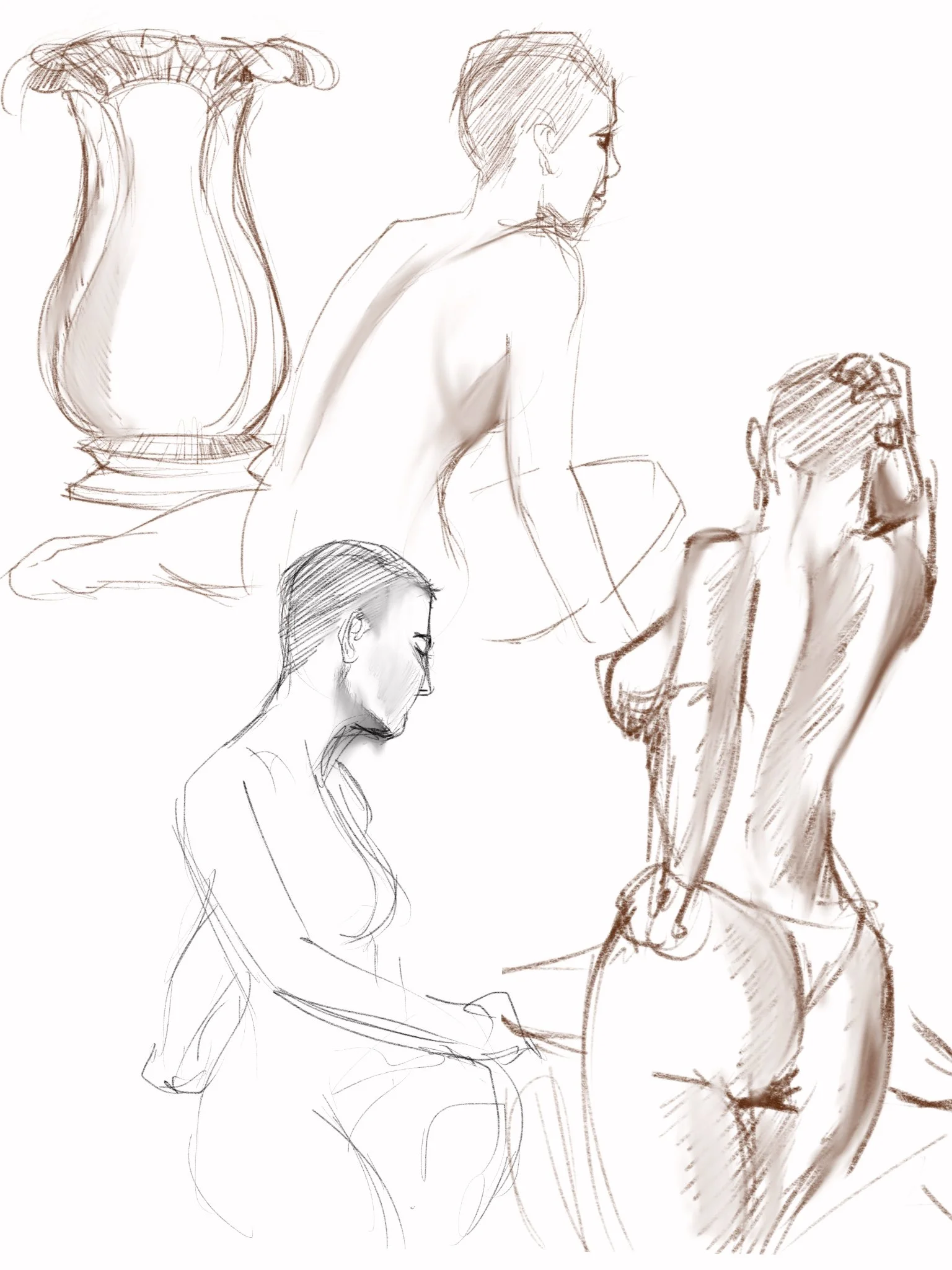

Believe it or not — if you can find a figure drawing session nearby that will truly take your figurative concepting to whole new heights. But if you don’t have that you’ve always got Pinnochio!

Pinnochio post Figure Session….

Every artist remembers the moment. You flip open a fresh sketchbook, pencil hovering, head full of possibility…and then the fog rolls in. You draw something. It’s fine. You draw something else. Also fine. But nothing feels right. Nothing feels like a character you’d want to keep, revisit, or introduce to the world.

This is where creative concepting earns its keep.

Concept design isn’t about drawing perfectly. It’s about discovering who or what you’re drawing through the act of sketching. For a brand new artist, this process doesn’t need to be complicated or intimidating. In fact, the simpler the steps, the more room imagination has to breathe.

Let’s walk through five approachable steps that help guide an artist from loose sketchbook exploration to a character they genuinely enjoy spending time with.

Step One: Start With a Spark, Not a Solution

New artists often begin with pressure. “I need to design a character.” That sentence alone can freeze a page solid. Instead, begin smaller. Begin with a spark.

A spark can be:

A mood (lonely, curious, stubborn)

A job or role (messenger, mechanic, librarian, monster babysitter)

A single visual idea (oversized coat, glowing eyes, mechanical arm)

A question (“What if a hero hated being brave?”)

Write this spark at the top of your sketchbook page. Not as a promise, but as a direction. You’re not designing a final character yet. You’re planting a flag that says, “Explore this.”

This step aligns with intention-setting. It gives your drawing session a compass without dictating the destination. When artists skip this, they often wander in circles, redrawing the same generic figure with different haircuts.

The spark is your invitation to play.

Step Two: Draw Badly On Purpose

Now some folks may call this drawing well; but in keeping with my current skill set this is more along the lines of concepting, because I’m intentionally keeping lines loose, and favoring shapes over details.

This step is crucial and frequently skipped.

Once you have a spark, your next job is not refinement. Your job is quantity. Fill a page with fast, messy, uncommitted sketches. Ten heads. Five bodies. Three wildly different silhouettes. Draw too thin. Too wide. Too tall. Too strange.

These are not failures. These are probes.

Think of this stage as asking visual questions:

What happens if the proportions are exaggerated?

What if the character slouches instead of standing proud?

What if their clothing tells a different story than their face?

At this stage, speed matters more than accuracy. Keep the pencil moving. Avoid erasing. Each sketch is a thought, not a verdict.

Many artists believe confidence comes from control. In reality, confidence grows from exploration. The more options you give yourself, the less precious any single drawing becomes.

This is where personality starts sneaking in unannounced.

Step Three: Choose What Feels Alive

After a page or two of loose exploration, pause. Not to judge, but to notice.

Circle the sketches that feel alive. Not the most polished. Not the most correct. The ones that make you curious. The ones that look like they have a story you haven’t fully heard yet.

Ask yourself:

Which sketch would I want to redraw?

Which one feels like it could move?

Which one surprises me?

This step teaches an essential creative skill: listening to your instincts. New artists often look outward for approval too early. Concept design asks you to look inward first.

Once you’ve chosen one or two promising sketches, redraw them slightly larger. Clarify the shapes. Strengthen the silhouette. Keep the energy, but give it structure.

This is the moment where a character begins to separate itself from the crowd.

Step Four: Add Story Through Design Choices

Now that you have a base character, it’s time to let design serve storytelling.

Every choice communicates something:

Clothing suggests lifestyle and environment

Posture hints at confidence, fear, or habit

Accessories imply history or purpose

Facial features can soften, sharpen, or complicate a personality

Ask simple questions and answer them visually:

Where does this character spend most of their time?

What do they value?

What do they need versus what do they want?

You don’t need a full backstory. A paragraph is enough. Sometimes a sentence is enough. The goal isn’t lore. The goal is coherence.

When design and implied story align, a character starts feeling intentional instead of accidental.

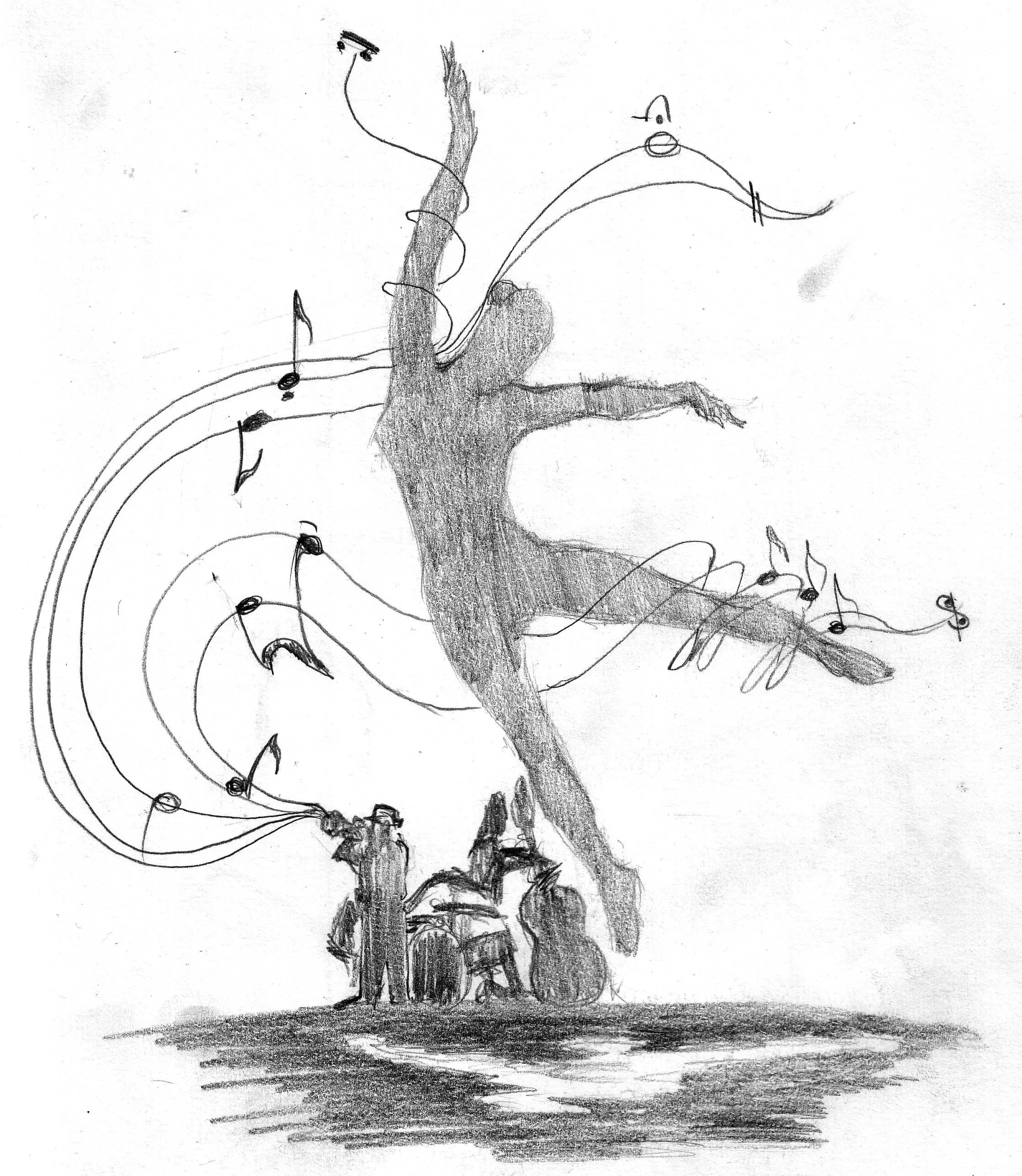

This is where many artists feel a sudden shift. The character stops being “a drawing” and starts becoming “someone.”

Step Five: Commit, Refine, and Let Go

The final step is commitment.

Choose one version and say, “This is who they are for now.” Clean up the drawing. Clarify line weight. Decide on a few consistent details. Maybe explore a facial expression sheet or a simple turnaround if you’re feeling ambitious.

But here’s the key: do not aim for perfection.

Concept design is iterative by nature. This version is not the last version. It’s a milestone. A snapshot of your current understanding of the character.

Let the character exist. Share it. Redraw it later. Allow it to evolve as your skills grow.

Artists who never commit stay stuck in endless exploration. Artists who commit too rigidly stop growing. The balance is gentle confidence paired with curiosity.

Closing Reflection: Characters Are Found, Not Forced

A character you like rarely arrives fully formed. They emerge through play, patience, and permission to explore imperfectly.

Your sketchbook is not a test. It’s a laboratory. Every page teaches you something about how you think, how you see, and how your imagination prefers to move.

When you approach concept design as a conversation instead of a performance, characters stop feeling elusive. They start showing up, one line at a time, ready to walk beside you into whatever story comes next.

Your journey becomes an adventure when imagination lights the way. 🌱📖